“No email was ever answered.”

“I was clueless about the process.”

“I didn’t feel they understood enough about abuse.”

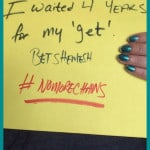

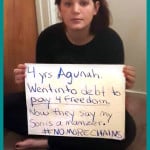

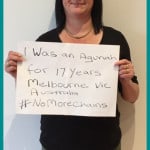

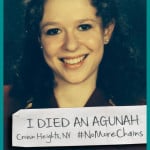

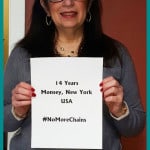

For hundreds of women and men navigating the divorce process in the Jewish court (beit din) each year, the journey is full of roadblocks. There is confusion about how the system works. Courts and judges lack training on domestic abuse, and the pressure to give in to unreasonable demands in exchange for a bill of divorce (“get”) and the freedom it brings is constant. Many women feel they are going through it alone, without the support and guidance of their leaders, communities, and the Jewish world at large.

To better understand where the system can improve, we created a survey to collect hard data about people’s experiences with the process of divorce in batei din around the world. Responses poured in from people around the Jewish world: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, South Africa, Australia, Israel, Brazil, and more.

When we created the “Beit Din Experience Survey,” we knew the results would be difficult to see. But we were not prepared for the heartbreak, grief, anger, and regret that are in the responses, which have been pouring in.

“He was violent, and I ended up in a shelter with my child and they wouldn’t help.”

“I was forced to sign away my marital property and much more in exchange for a get.

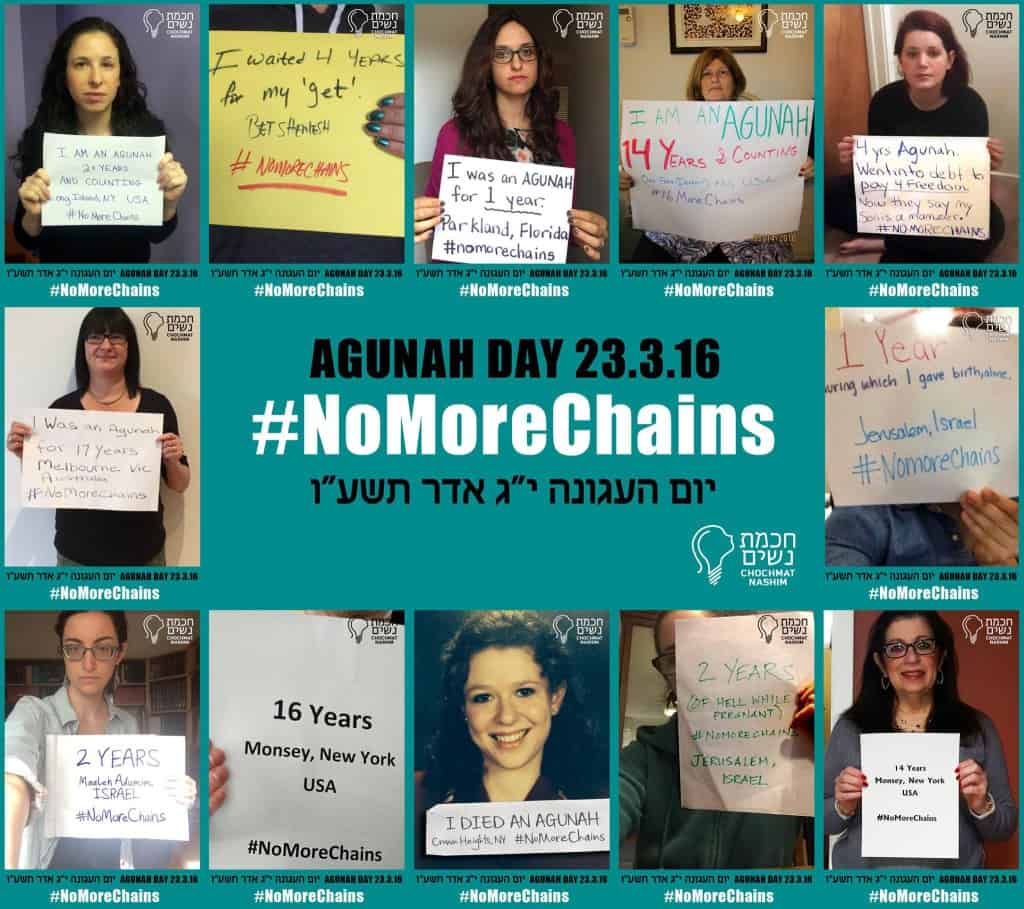

Get-abuse is a serious problem all over the world, in every denomination and segment of the Jewish community. This abuse has many faces. It can look like financial extortion. It can manifest in demands on custody agreements. It can present as a demand to give up the rights to one’s marital home. When the full picture of get-abuse becomes clear, what becomes even clearer is that it is far more common and far-reaching than we think.

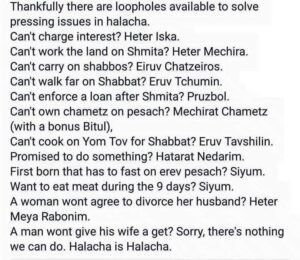

But we also know that when batei din have proper training, oversight, and accountability, they can provide fair and wise forums for navigating difficult divorces. We know that when communities take proactive steps to address get-refusal by implementing tools such as halachic prenups and synagogue bylaws, instances of get-abuse go down. We know that by refusing to stay silent on this critical issue, agunot (the women chained in unwanted marriages) will not have to struggle alone — instead, they will feel the love and support of all of the Jewish people behind them.

The Jewish community does not have to — and indeed must not — accept get-refusal in our midst. The sanctity of Jewish marriage is severely damaged when women wait years for their freedom. Unlike tragedies that strike at random, get-refusal is something we can solve, if we, as a community, are determined to do so.

* * *

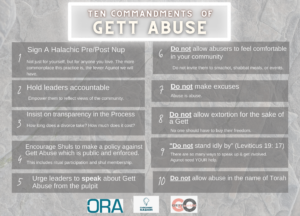

As we observe International Agunah Day, remember that, like Esther and Mordechai, you can be the voice our community needs to address this injustice. See our Ten Commandments of Gett Abuse below, print a copy for your shul or organization, and together let’s remove the nightmare of get-refusal from our midst, and create a community where Jewish marriage has integrity and no one is held hostage or abused in the name of Torah.

The 10 Commandments of Get-Refusal

To demonstrate each commandment, we have excerpted a real survey response from people who have personal experience in a Jewish divorce court.

- Sign a halachic prenup/postnup

“I did not have a prenup and the man I married was an abusive criminal.”

2. Hold leaders accountable

“The dayanim (judges) need to understand that they are dealing with very vulnerable people.”

“I was repeatedly singled out and shamed because I was a woman asking for a divorce.”

3. Insist on transparency in the process

“They delayed the date three times”

“There was a lack of steady communication.”

“I didn’t get guidance beforehand.”

4. Encourage shuls to make a public and enforced policy against get-refusal

“I didn’t’ feel like there was any support.”

“This process truly turned me away from Orthodoxy.”

5. Urge leaders to speak about get-abuse from the pulpit

“I never feel listened to.”

“My (ex) husband started to say something about withholding the get, and the rabbi cut him short and said, very firmly, “We are not going there.”

6. Do NOT allow abusers to feel comfortable in your community.

“The issue is that the beit din does not understand narcissistic abuse.”

“They did not understand how he was being abusive and using them to manipulate me.”

7. Do NOT make excuses

“They contacted my ex about the get. He says he is not withholding, but waiting and the beit din will do nothing.”

8. Do NOT allow extortion for the sake of a get

“The sad fact is that I had to pay extortion fees for my get, and even today, I am still paying off the debt.”

“All the things that happened were out of fear that he would make me agunah. I ultimately gave up asking for any money because of that fear.”

“At one point, a rabbi told me that I had a gun to my head so to speak — that I should give in to the guy’s demands.”

9. Do NOT stand idly by

“He was violent and they wouldn’t help.”

10. Do NOT allow abuse in the name of Torah

“There was no sensitivity to my survival of domestic abuse.”

* * *

The Ten Commandments of Gett Abuse and this survey are a joint project of Chochmat Nashim, GettOutUK, and ORA — three organizations in three countries which see the same failures in the system, and the same opportunities for change in the community.

The future of Jewish marriage matters to us all. And contrary to what many say, agunot do not have to be an inevitable part of Judaism. The women and men chained in marriage today are not victims of tragedy, but victims of abuse. We can, and must, end this shame by refusing to accept get-refusal and by insisting on proper training for the courts’ judges.

Please join us.

If you would like to sign a halahic pre- or postnup to add your voices to the thousands who want to see an end to get-abuse, write to info@chochmatnashim.org with your name and the country in which you live.

If you have experience seeking divorce in the beit din, add your voice to the survey in English outside of Israel, for experience in Israel, or in French for batei din outside of Israel.

—

The above was co-authored by Shoshanna Keats Jaskoll (Chochmat Nashim), Keshet Starr (ORA), and Ramie Smith (GettOutUK).

Originally published on The Times of Israel