The Stamford Hill protest (Laura ben David)

On a dreary March morning in Stamford Hill, 10 of us stood in Clapton Common holding signs in English and Yiddish.

A woman walked past us and slowed her stride, careful not to stop, as though aware that others were watching. “Thank you,” she said, her face a mask of controlled but pained emotion. “Thank you for doing this. It’s so important… I waited for so long and no one showed up for me.”

And then she was gone. Just another Chasidic woman with a cropped modest wig covered with a secondary head covering, blending into the streets of Stamford Hill.

We looked at one another, struck silent. The exchange, just seconds long, had put tears in our eyes. Though we were there for one woman, Leah Hochauser, who had been waiting eight years for her get, it was clear that our actions could affect so many more.

The protest was, as far as we know, the first of its kind in Stamford Hill. We called for Chaim Yeshaye Hochauser to free his wife and grant her a get.

Though he has been called at least five times to Keddasia Beis Din, he has not shown up. His ailing wife, Leah, simply wants to be free of her dead marriage. Aside from the emotional turmoil caused by being denied a get, Leah also suffers with a serious medical condition. Hochauser doesn’t seem to care.

Numerous people stopped to talk to us, men and women. Some stared, others recorded us and still others yelled, asking why we were doing this in public.

A number of people sympathised, but didn’t understand what they could possibly do to help. A few said they would speak to him.

In reality, however, get refusal is everyone’s problem and everyone has a role in resolving it. It is a man-made problem which calls for man-made solutions.

According to Ramie Smith of GettOutUK, which represents people seeking Jewish divorce (Leah is their current client, along with 10 other Jewish women): “Men who withhold a get have no consequences. The woman suffers, raising her children, often in poverty, alone and feeling helpless. By showing a man that his neighbours will know that he is abusing his wife, that he is ignoring the Beis Din order to appear, we can have an impact. We hope that Stamford Hill will come together as a community and convince Chaim Yeshaye to end his abusive behaviour, freeing Leah to live her life.”

In the past year-and-a-half, GettOutUK has helped 13 women gain their freedom. Their stories are extremely difficult to hear.

But hearing them is imperative if we are going to heal the nightmare that Jewish divorce has become. And we as a community can end it. During my visit to London earlier this month, we sat with nine former and current agunot.

The women ranged in age from 25 to 65, with one woman having been alive for as long as another had waited for her freedom. They also ranged in religious observance, from strictly-Orthodox Chassidic to non-observant.

While every story is unique, themes and patterns emerged during this conversation which we, the community, need to understand and address.

Every woman who has a Jewish wedding is a potential agunah, and men can also be trapped.

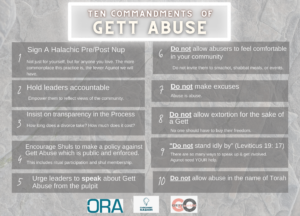

Together we can end this nightmare if we make certain behaviours and practices standard. With that in mind, we created the 10 Commandments of get abuse to help the community end get refusal:

1) Sign a Halachic pre- or post-nuptial agreement. While a bit more complicated in the UK, this is becoming standard around the world as a community vaccine for get refusal;

2) Hold your leaders accountable. Ask what they are doing to safeguard the integrity of Jewish marriage;

3) Insist on transparency in the Jewish divorce process, asking how long a divorce takes and how much money it costs;

4) Encourage synagogues to define a policy against get abuse which is public and enforced. This includes barring refusers from ritual participation and shul membership;

5) Urge religious leaders to speak publicly about get abuse from the pulpit;

6) Do not allow get abusers to feel safe and comfortable in your community. Do not invite them to shabbat meals, or communal events;

7) Do not make excuses. Abuse is abuse;

8) Do not allow extortion for the sake of a get. No one should buy their freedom;

9) “Do not stand idly by” (Leviticus 19:17). It is our job to get involved;

10) Do not allow abuse in the name of Torah.

Adopting these measures is a first step. You never know who you can save by speaking out.

Originally published on The Jewish Chronicle